Corporate entry: Catholic Church

- Functions

- Religion

- Alternative Names

- Roman Catholic Church

Details

The Spanish expeditions to the Solomons in 1568, 1595 and 1605 were for exploration, colonisation and spreading the gospel. Mendaña abducted some Solomon Islanders from Makira, who ended up in Peru before they disappeared from history-the first Solomons Catholics, at least in a rudimentary way. (Laracy 1976, 11)

In 1836, the Sacred Congregation for the Propagation of the Faith (Propaganda) in Rome made the Western Pacific north and south of the equator a distinct mission area for the Society of Mary (the Marists), a new religious order. (McCabe 2004) Initially, they were under the control of the newly created Vicariate of Eastern Oceania, but they agitated for independence and in 1842 the Vicariate of Central Oceania was created, stretching from Samoa to New Caledonia. Friction continued, and in 1843 the Marists were granted a new vicariate in Melanesia and Micronesia. Jean-Baptiste Epalle (q.v.) was consecrated Bishop. The new diocese covered the whole of New Guinea, Solomon Islands and Micronesia, but not the New Hebrides or New Caledonia, where they also settled in 1843.

The French Marists first reached the Solomon Islands on 2 December 1845, led by Bishop Epalle. Their first stop was at Makira and they then moved on to Isabel. There, Epalle was killed almost immediately when his party landed at Astrolabe Harbour, Thousand Ships Bay. The remainder of the party of seven priests and six lay brothers tried to settle on Makira at Makira Harbour. The site was chosen for its port and also because they had met Loukou from the Mahia descent group, who had worked for some years as a cabin boy on an English ship and was willing to act as their interpreter. They had brought substantial supplies with them, including animals, and they even planted cuttings brought from France-grapes, olives, oranges and figs-and tobacco. Their tobacco, figs and oranges grew well but the grapes perished. Their hired ship, Marion Watson, departed for Sydney carrying three of the missionaries and the news of Epalle's death. In 1847, Father Collomb, who had travelled back to Sydney, returned to Makira on 28 August as Bishop-elect. Four of the Marists had died in his absence. The sailors from the ship caused trouble with local women and many of the party were sickened by malaria. The Makira Mission had lasted twenty months, and Collomb now decided to move on, to Woodlark and Umboi (1847-1848) in the islands off eastern New Guinea, and finally to Tikopia (1851-1852), both areas known to whalers.

The Tikopia venture was in the hands of Father Gilbert Roudaire, born in 1813, ordained in 1842 and then appointed to the Pacific. After time on Wallis Island and New Caledonia, in 1849 he became aware of the Polynesian community on isolated Tikopia. He gained permission to go there and arrived on 12 December 1851 with his colleague Father Douarre. They were isolated for several months, until June 1852 when another ship visited carrying Brother Michel (blood brother of Father Douarre). No news was heard from Tikopia for some time, which caused the Marist procurator in Sydney to charter a ship in January 1853 to travel there. On arrival he found no sign of the three Marists and no clear picture of what had happened to them. They may have left the island on the ship Etoile du Matin in 1852, which records show was lost at sea. (Golden 1993, 21) After the 1845-1853 failures, and nine missionaries dead, no more attempts at Catholic missionary colonization in the Solomon Islands were made for several decades. (Wiltgen 1981, 330-346; O'Brien 1995, 57-88; Laracy 1976, 11-31)

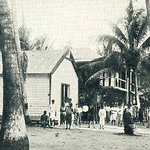

In 1875, the Propaganda was reminded that Micronesia and Melanesia were without a Catholic presence at a time when other denominations were busy carving up the Pacific into Christian territories. After the Marquis de Ray's disastrous attempt at colonisation in New Ireland (1879-1882), which involved Catholic priests, the vicariates were transferred to the Missionnaries du Sacré Coeur d'Issoudun (MSC), the first party from which arrived at Rabaul in 1882.They had no capacity to take on the Solomons as well and requested help from the Marists, although the Marists did not want to share and the MSC was not keen to surrender the German Solomons. A German order, the Society of the Divine Word (SVD), began work on the north coast of New Guinea in 1896, and because of the tensions between orders, the Solomons was split into two prefectures apostolic, the British Solomons administered from Fiji (1897) and the German Solomons from Samoa (1898). A final change occurred after the political map was redrawn in 1899 and the German New Guinea border was withdrawn to Bougainville and the Shortland Islands. In 1904, the names of the prefectures were altered to North Solomons and South Solomons. Mission stations typically consisted of a church and presbytery, a convent and classrooms and dormitories for students. Usually there was also a dispensary for medical treatments, and a plantation to provide food. (Laracy 1976, 37-38)

Under the auspices of the Oceania Marist Province, Catholic missionaries returned to the Solomons in 1898 when Bishop Julian Vidal landed at Tulagi in May with three Marist priests and nine lay assistants. They chose to settle on small Rua Sura Island off Aola Bay, Guadalcanal, where a few traders resided. They purchased the island for £100 from one of them, Samuel Keating, who claimed to have himself bought the land in 1894 from a chief named Wylia. (Laracy 1976, 40) Further visits were made in 1899 and 1901, and then in 1903 Vidal was succeeded as Prefect Apostolic of the Southern Solomons by Jean-Ephrem Berteaux. Marist Catholic missionaries arrived at Avuavu (Loqu or Longu) on Guadalcanal's Weathercoast in October 1899, but did not stay long. In 1900, the Resident Commissioner approved their purchase of land at Marau Sound and also at Tangarare further west along the Weathercoast. (O'Brien 1995, 102-120)

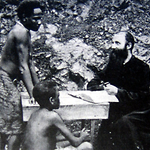

The Catholic Mission faced local opposition at Rua Sura; the people had easy access to trade goods from resident traders, did not acknowledge the land purchase, and feared the Protectorate and religious incursion. Slowly, the Marists wore down their opposition by hiring labour through one of the traders, Lars Svensen, and through the good work of Father Pierre Rouillac. He brought the initial students from Makira and Malaita and managed to acquire land and more students at Moli on the Weathercoast. (Laracy 1976, 41-42; O'Brien 1995, 198-199) Rouillac also made progress at Avuavu west of Moli, obtaining land and thirty-six students for Rua Sua. Two priests spent six months at Avuavu in 1899 and returned in 1901, establishing a strong base there by about 1913. Father Jean Coicaud began work at the Avuavu Mission in 1902 and was joined in 1907 by Father Jean Boudard, who remained there until 1942. The first formal school classes began in 1909. (Kabutaulaka 2002, 24)

Solid beginnings were made at Tangarare in May 1898, where Rouillac purchased land and two priests were installed in June 1900. Also that year, the Marists purchased land at Vaturanga near the Anglican base at Maravovo at the northwest tip of Guadalcanal, although Resident Commissioner Woodford refused to confirm the transaction because it was too close to the Anglicans. There was an unofficial policy of 'comity' between the Protestant Christian missions, which the Catholics refused to observe, even though Woodford seems to have offered the Marists sole access to the rest of Guadalcanal. (Laracy 1976, 43-44) Woodford changed his attitude a few years later and granted the Marists land at Visale (q.v.) in 1904, just thirty-two kilometres east of Maravovo. Rivalry continued between Visale and Maravovo; the Anglicans decried the French presence and boasted of their large ship the Southern Cross (q.v.), and the Catholics countered by building a stone church at Visale (q.v.) in 1910, the only stone building in the Solomons at the time. By 1914, they claimed to have baptised 1,300 as Catholics on Guadalcanal. Although the Marists suffered some failures (Aola 1905), Moli (1903-1907) and Savo (1909-1911) and ended up concentrated at Rua Sura, Avuavu, Tangarare and Visale, they always had more staff on Guadalcanal than did the Anglicans. In 1914, the Catholic Mission had twenty-four priests and fourteen sisters on the island (AR, 1913, 4); in 1920 it had eleven Marist priests, two lay brothers and four nuns there, while there was only one Anglican priest. (Laracy 1976, 44-45; O'Brien 1995, 124-126)

In 1900, the Protectorate's Annual Report recorded thirteen Catholic Mission staff-eleven priests and two sisters. The missionaries established a temporary presence on Savo Island in 1900. The Catholics arrived at the Shortlands in1898, and in 1903 Marist missionary Father Josef Forestier arrived on Tambatamba Island off Choiseul. (O'Brien 1995, 151-156) The Mission's ship the Eclipse was wrecked in 1902, leaving the Marists with poor inter-island transport, usually only the small schooner Verdelais. Then, in 1909, they acquired the 30-ton Jean d'Arc, which enabled them to begin turning their attentions to Malaita and Makira. (Laracy 1976, 45; O'Brien 1995, 118, 200-203) During 1908-1909 the Mission began looking for a site on Malaita and chose Tarapaina in the 'Are'are language area, at Hauvarivari Passage, Small Malaita in 1910, and Rohinari in the 'Are'are' Lagoon in 1912. They tried Makira again in 1906 and 1908, and in 1911 entered New Georgia at the invitation of trader Norman Wheatley, who was seeking a counter-balance to the dominant Methodists. The Marists eventually withdrew from New Georgia in 1912 after meeting antagonism from Roviana Lagoon people and when Woodford refused to confirm their purchase of land. Their withdrawal enabled the Marists to concentrate their expansion efforts on Malaita, and they moved north on that island to Mbuma and Langalanga in 1909, to Rokera in 1929 and to Takwa in 1935. (Laracy 1976, 48-49; O'Brien 1995, 122-129, 137-155, 173-182)

The South Solomons prefecture was elevated to an apostolic vicariate in 1912 (including Guadalcanal, Makira and Malaita) with the same elevation granted to the North Solomons in 1930 (Buka and Bougainville). In the South Solomons, the rather vain Jean-Ephrem Bertreaux, a priest on Guadalcanal since 1903, was consecrated as Bishop and managed to have Isabel (where Epalle had been killed) transferred to the South Solomons. (O'Brien 1995, 129-130, 246) A Vicariate of the Western Solomons was established in 1959, excised from the first two, which included Isabel, New Georgia and Choiseul. After 1967, the vicariates became known as dioceses. Catholic development was directed from the Mission station at Visale, Guadalcanal, before World War II, and from Honiara after the war. Convents were established at various Mission stations: Tangarare (1904), Visale (1908), Rua Sura (1911), Avuavu (1913), Wainoni Bay (1915), Ruavatu (1927), Mbuma (1928), Rokera (1933) and Takwa (1937). (Laracy 1976, 50)

Bishop Bertreux died in 1919 and was succeeded by Bishop Louis Raucaz, another experienced missionary. In 1923, Visale replaced Rua Sura as the Marist headquarters. The substantial Visale Cathedral was destroyed in a severe earthquake on 25 January 1925 and rebuilt in 1930. (AR 1925-1926, 3; NS 14 Feb. 1968) Visale had an imposing Cathedral containing the remains of Bishop Epalle (which were lost in bombing during the war), a printing press, an electric light plant, a telephone service, a movie projector and an excellent water supply. There was also a boarding school for 150 boys and girls. The common language was French, spoken by all members of the Mission staff. The first language of instruction was Ghari, with mission texts produced from the 1900s in Ghari and other languages. Ghari never became the Mission's lingua franca in the way that Mota did for the Melanesian Mission and instead Pijin English was adopted as the main language of communication with villagers. All mission staff were expected to learn the languages of the areas to which they were assigned. (O'Brien 1995, 211-216; Laracy 1976, 54-59) Bishop Raucaz died from malaria in June 1934 and was succeeded by Jean Maria Aubin, who remained Bishop until he was seventy-nine.

The North Solomons prefecture did little to impinge on the BSIP. They began work in the Shortlands in 1899, but conversions were slow, partly because the chiefs were polygamous and had no wish to give up their array of wives. A major station was Poporang Island, southeast of Shortland Island, which became the pivot for other activity in the Western Solomons. Choiseul was visited in 1903 and 1909, but no progress was made. Similar visits to Mono in 1908 and 1910 were also unproductive because of old animosity with the Shortlands, and the Mission eventually lost out to the Methodists. Antagonism with the Methodists and the newly arrived Seventh-day Adventists continued, with constant complaints that holy medals were being snatched from the necks of Catholic converts, and great rivalry between the Marists and the long-staying Methodist leader Rev. John F. Goldie. The most heated competition was on Choiseul, where the Methodists had begun proselytizing in 1905. The Marists visited Choiseul in 1903 and established themselves at Tambatamba River in 1912. When the priest there was invalided to Sydney the station was operated ineffectively from Poporang until 1920. Another failed attempt to establish a permanent Choiseul base was made between 1920 and 1925, after which the few Catholics on Choiseul were once more serviced from Poporang until a permanent presence was finally established in 1931. (Laracy 1976, 54-59)

In the South Solomons, the Church claimed 3,436 Catholics in 1918: three thousand on Guadalcanal, three hundred on Makira and 136 on Malaita. The growth area was Malaita, which by 1936 had 3,000, although that number was still exceeded by Guadalcanal with 5,000. In 1942, there were 20,000 baptized Catholics in the geographic Solomon Islands, but only one-third of them were in the Protectorate. By 1947 the Malaita count had reached 6,000, exceeding Guadalcanal. (Laracy 1976, 65; O'Brien 1995, 202-205)

Compared with the other denominations, the Catholics were slow to develop good quality medical services and schools. New medical policies began to emerge in the 1930s, carried out by lay staff as well as clergy and the new Marist Mission Medical Society, which recruited nurses for the North and South Solomons. They also began to combat the clear Protestant superiority in the area of education, with the intention of transferring knowledge and confirming identification with Catholicism. The first thing the Catholic clergy always did was to learn local languages, and most Marist education was in the local vernacular. Early in the twentieth century, there had been no curriculum and teaching was haphazard, fully dependent on the skills of the local priest. Unlike the Protestant churches, the Catholics focused on knowledge transmission by their priests and did not use indigenous teachers, although they did foster catechists as assistants. There was an attempt to found an indigenous Brotherhood at Rua Sura in 1912, but it failed due to over-emphasis on using the men as unpaid agricultural workers. In the 1920s, Bishop Raucaz tried to open a catechist school at Gausava near Tangarare in 1928, which also failed. Ructions over catechists led to boycotts of Tangarare and Visale in the 1930s, which lasted until 1936. (Laracy 1976, 92-103)

The Marists had more success with the founding of the Daughters of Mary Immaculate in the Southern Solomons-a sisterhood to supplement the work of European nuns-and a similar congregation in the North Solomons, the Little Sisters of Nazareth. (Laracy 1976, 107) Then, in 1950, the Anglican Sisters of the Cross Order (q.v.) transferred to the Catholics.

During the Second World War, Bishops Aubin and Thomas Wade (North Solomons) and their Marist priests, brothers and nuns went into hiding within the Solomons. This followed a missionary tradition that accepted possible martyrdom, although many of the sisters were later evacuated to New Caledonia and Australia. For some of the evacuated original clergy, particularly sisters, this was their first time outside of the Solomons since their arrival early in the century. The first Japanese contact with the Marists was in the North Solomons, where they were paroled so long as they did not contact American or Australian authorities. Their food was commandeered and their radios were confiscated. Early relations were amicable, but Bishop Aubin refused to help recruit labour for the Japanese development of what later became the Henderson Airfield and once the Americans landed on Guadalcanal relations cooled because the Japanese were suspicious of possible Marist collaboration with the Allies. Two sisters were killed at Tasimboko (Tadhimboko or Tathimboko) and a third fled to the care of coastwatchers, and four missionaries at Ruavatu were bayoneted. Visale became unsafe, forcing Aubin and his staff to move to Tangarare. The American commander ordered their evacuation: between October and December two Marist priests, eight brothers and nineteen sisters left the Solomons, most to New Caledonia. Aubin was allowed to stay, along with six priests on Malaita and two on Makira. At Wainoni, Makira, another priest and two nuns refused to leave and since the Japanese never reached that island they managed to keep the Mission station running at close to normal. Another priest, Emery de Klerk of Tangarare, joined the Labour Corps as a recruiter and intelligence adviser. Once the war turned against the Japanese the Marists in the South Solomons were fairly free of the conflict, but those in the North Solomons continued to suffer and some were killed; Bishop Wade and his remaining staff were forced to leave. The final death tally was two priest and two nuns killed in the South Solomons and four priests, six brothers and two nuns in the North Solomons. (Laracy 1976, 110-157)

In the South Solomons the war destroyed the Visale, Ruavatu and Marau mission stations, and in the North Solomons all stations except Poporang. When staff returned after the war they had to begin from nothing, and, particularly on Malaita and Makira, Maasina Rule (q.v.) created a new social and political environment. The Marists fared quite well from their relationship with Maasina Rule (q.v.), gaining many converts, though one by-product of the movement was land claims against the Marist stations on Malaita, particularly at Tarapaina. In March 1950, the Marists under Father van der Walle began the Catholic Welfare Society (CWS) to enhance the spiritual and material welfare of all Catholics, but, unlike Maasina Rule at that time, in support of the BSIP Government. The government was initially happy with the CWS but became suspicious that it was a front for Maasina Rule, and in September Resident Commissioner Gregory-Smith visited Rohinari and ordered the CWS dissolved. It was revived in 1953 and in 'Are'are in the longer term translated into social action and welfare movements. The Church and the CWS finally separated in July 1961. (Laracy 1976, 128-134; O'Brien 1995, 183-188)

After the war, Bishop Aubin settled in a small house at Kakambona just outside of Honiara. Initially, a leaf chapel in Honiara was used each morning as a church for the Langalanga wharf labourers, and by day as an office. The remains of the Visale printing press were brought to Honiara and set up at Kakambona, where the Bishop made his headquarters at Tanagai. St. John's School was built at Rove, and Villa Maria Training College was built at Visale on the foundations of the old church, taking its first students in 1959. A temporary Holy Cross Pro Cathedral was built on a hill where it was thought that Mendaña had planted his cross in 1565. Like the Anglican's temporary cathedral, it was a large Quonset hut left over from the war.

The Church recognised the need to train indigenous priests and in 1946 sent twenty students to Fiji to study to become Marist brothers. All but three completed the course and three became Native Medical Practitioners (q.v.). Teacher training began at Keita in 1949 and at Tarlena in 1953 (both in the North Solomons), and at Visale in 1961, following the British Solomon Islands Training College (q.v.) curriculum. (Laracy 1976, 155) A teacher-training school for girls was begun at Asitavi in 1957. In 1951, a minor seminary was started at Tenaru near Honiara in a large Quonset hut the Americans had left behind near St. Joseph's School. (O'Brien 1995, 221) Priests and nuns were no longer allowed to teach without having formal qualifications. (Laracy 1976, 147-150) The Church became involved in two leprosaria staffed by Marist sisters, at Tetere near Honiara and at Piva near Torokina. Hugh Laracy observes that Catholic schools changed after the war-once an adjunct to evangelism, they now more professionally prepared Catholic Solomon Islanders for their new roles in the Protectorate. The priests spent more of their time in the classroom, there were more lay volunteers involved, and a government curriculum was followed. There were ever-growing numbers of indigenous teachers to an extent that in the mid-1970s they made up almost all primary school teachers. (Laracy 1976, 144; O'Brien 1995, 224-226)

The Church also had to accept BSIP government initiatives, such as the changes which followed from the appointment of C. A. Colman-Porter as the new Director of Education in 1947. A November conference was organised for all educators and a new policy outlined to create state learning institutions to provide skills the Protectorate needed in teaching, nursing, agriculture, commerce, carpentry and engineering. The only concession to the churches was a plan to allow colleges within them that would be organised according to religious denominations. This development was delayed when Coleman-Porter resigned in 1948 after he realised that he did not have the support of the government. (Laracy 1976, 151-152) A new conference was held in March 1949, organised by Howard Hayden, Education Adviser to the WPHC, which was no more conciliatory toward the churches than the 1947 conference had been. New BSIP education regulations were circulated in 1953 that stipulated new multi-course colleges to produce practitioners in all of the skills needed to develop the Protectorate.

Nonetheless, government aid to mission schools continued to increase during the 1960s and 1970s until the government took over most church primary schools in the mid-1970s. The first Catholic high school opened at Aruligo near Honiara in 1967 with a full graduate staff. However, just as the Catholics were not interested in 'comity' with the Protestants, they also had no desire to give up control of their schools, which were such a basic part of engendering Catholic culture. (Laracy 1976, 144-147)

In December 1966, Pope Paul VI established a new ecclesiastical hierarchy for Papua New Guinea and the Solomon Islands, which came into being on 1 January 1967. The Archdiocese of Rabaul was created to contain four dioceses: Kavieng, Bougainville, Honiara and Gizo. The two Mission apostolic vicariates each became diocese in their own right. The Vicar Apostolic of the South Solomons, Daniel W. Stuyvenberg (q.v.), was styled Bishop of Honiara, and Gizo Diocese was under Irishman Bishop Eusebius Crawford. Both were to be suffragans of the Metropolitan See of Rabaul. Dominicans ran the Gizo-based diocese, and Marists the Honiara-based diocese. There had been discussion about introducing the Dominican Order since 1937, in recognition that the Marists lacked the capacity to serve all of the Solomons, but the war halted progress and it was not until January 1956 that Dominican priests, friars and sisters set out from Australia to Gizo. They purchased Loga, an old Lever Brothers plantation a short canoe trip from Gizo, and set to work. They also purchased a Mission ship, the Salve Regina. In 1959, the Western District became an apostolic vicariate in its own right under Bishop Crawford. (O'Brien 1995, 157-170)

Bishop Stuyvenberg represented the National Catholic Relief Services and became distributing agent for the U.S. government AID Food Programme in the Solomons until 1968, when the position covered the region as far as Tonga. The new Honiara Diocese was formally proclaimed in Holy Cross Cathedral on 25 January 1967. (PAMBU Catalogue; Fox 1958, 97-98, 202; Edridge 1985, 242; SS 13 Oct. 2005; NS 19 Dec. 1966, 7 Feb. 1967; AR 1968, 84)

At Visale, a new church was dedicated in October 1966, able to hold eight hundred. The first Solomon Islander to be ordained as a priest was Michael Aike (age twenty-five) from Rohinari, Malaita, on 10 December 1966. He was followed in December 1967 by Donasiano Hitee, thirty-three, from Tarapaina in South Malaita, and, also in 1967, Timothy Bobongie, twenty-nine, from Kwaloai in Malaita's Lau Lagoon. The fourth Solomon Islander to be ordained was Lawrence Isa from the Shortlands, raised to the priesthood by Bishop Crawford at Gizo in 1968. Two more were ordained in 1970: Kamillo Deke of Guadalcanal, and Francis Mauli, ordained at Mbuma, Malaita. (NS 21 Feb. 1966, Dec. 1967; AR 1966, 70, AR 1968, 85, AR 1969, 82, AR 1970, 90)

During 1966, buildings were constructed at Aruligo, Guadalcanal for a new St. Paul's Secondary School, expected to open in February 1967 with a staff of four graduate teachers. Ten to twelve voluntary lay helpers (artisans and schoolteachers) from Australia, New Zealand and Hong Kong donated their services for different works of the Church during 1966 and 1967. (AR 1966, 70, AR 1967,79)

During 1967 Honiara was raised to the status of a parish and the Order of Solomon Islands sisters, Daughters of Mary Immaculate, continued to grow. Three completed their novitiate in December and took their vows as nuns, bringing the total in the Order to seventy-four. They were able to staff eight of the Church's convents and two completed their training as nurses at the Central Hospital. During November 1966 a cyclone did considerable damage to Church property; the church at Wagina, Manning Straits had to be rebuilt and the Salve Regina was rebuilt and resumed its normal sailing schedule. (AR 1967, 79) In 1968, the Catholic Church continued to expand its outreach on Choiseul and Makira in the fields of education, medical welfare and community development. The extension of the Church's work in the Western District brought additional priests and sisters from Australia. The Catholics also cooperated with OXFAM and the Foundation for the Emerging Peoples of the South Pacific to distribute aid. Plans were laid to begin a tuberculosis hospital on Malaita, which opened at Rohinari in 1969, the upkeep to be undertaken by the local community. (AR 1968, 85, AR 1969, 82)

During 1970, church work continued in the fields of education, medical welfare and community development. A significant change was the removal of the junior primary schools from the Mission stations to the villages, where the children could be educated close to home and in their own environment. Father John Roughan continued to have an effect at Rohinari, Malaita, where a community development project using labour freely supplied by the local people operated coconut plantations, raised cattle and built ships. Limited aid from overseas financed the Rohinari and other development projects. The Gizo Diocese announced plans to establish a Community Development Centre at Monga, Kolombangara under the joint supervision of the Marist Teaching brothers and the Dominican sisters. Its purpose was to provide post-primary education, with courses on special skills useful in village life, especially agriculture and domestic science. In 1970 the first Solomon Islanders were presented to Pope Paul VI, five sisters of the Church of the Holy Father who travelled to Australia with Bishop Stuyvenberg. (AR 1970, 90)

The Church recognized that primary school leavers needed special training for life and work in their villages, and in 1971 initiated a number of pilot projects. St. Dominic's Community Centre was opened at Vanga Point, Kolombangara in January with twenty boys and seventeen girls of post-primary school level and a staff of two Marist teaching brothers, two Dominican sisters and a resident chaplain. At the Di-Vit Centre near Tenaru, girls were trained in home craft and general leadership by a staff of one European sister and two Solomon Island sisters of the Daughters of Mary Immaculate. Rohinari, Malaita, trained students in book-keeping and running a store, and Wainoni Bay, Makira, provided agricultural training with the help of a volunteer with an agricultural degree. The Church also encouraged and gave use of facilities to socio-economic projects carried out entirely by Solomon Islanders. In this way, a ship for the transportation of market produce was built on the Mbuma slipway and a trade store opened adjacent to the Rohinari Mission.

The Church decided to relocate its secondary school from St. Paul's Aruligo to St. Joseph's Tenaru on the outskirts of Honiara. Form I was the first to move in 1972. The transfer of all junior primary schools from mission station grounds to villages continued, and the staff of all junior primary as well as several senior primary schools were localised. Localisation also continued in the priesthood and administration, including the Cathedral in Honiara. Solomon Islands priests took part in a meeting at Port Moresby, which reported to the Conference of Bishops on the state of the Church in the Solomons. During 1971, the Bishop of Honiara was elected to represent the Solomons Conference of Bishops at the Synod of Bishops in Rome. (AR 1971, 99-100)

In 1971 and 1972, cyclones greatly damaged Church property on many stations; on at least five this was severe and one was completely destroyed. Rebuilding was undertaken with help from overseas although this also delayed the existing building programme. As Honiara grew, it was decided to build a second church, which was opened at Kukum on July 1972. The intake of the rural training school for girls at Tenaru increased and became inter-denominational. The year was also a milestone in the congregation of local sisters, which the Pope had approved as a recognized order of nuns twenty-five years earlier. The congregation had expanded to eighty-two professed sisters who were working in all branches of the Catholic Church and for the people as teachers, nurses and domestic-trained sisters, and village based sisters. The move of the secondary school from Aruligo to Tenaru was slowed by difficulties with the building programme, and it was not completed until mid-1973.

Two meetings were held by the Pastoral Council, which contained representatives from all the parishes in the Honiara Diocese. The Young Catholic Workers (YCW) were active in organizing all kinds of sports and recreations for Honiara's young people, and also went on long weekend camps. Localisation continued with the appointment of a local priest as Vicar-General of the Diocese and the election of another to be a member of the Bishop's Council. The last link with the original founders of the Catholic Church in the Solomons was broken on 6 October 1972 with the death of Rev. Fth. Halbwachs in Ruavatu. He had arrived in the Solomons in 1909 and survived all of the other early missionaries, reaching the age of ninety-one. (AR 1972, 106-107) He would have been pleased that at the time of his death there were five indigenous priests and eighty-two indigenous sisters in the Honiara Diocese, and seven indigenous priests and thirty-six indigenous sisters in the Bougainville Diocese. Perhaps he would have been less happy with the Gizo Diocese with its single indigenous priest. (Laracy 1976, 159)

In 1973, in the Gizo Diocese in Western District, the first graduates of St. Dominic's Community Development Centre at Vanga Point completed their course in post-primary preparation for a more developed village life. The second group of local women was professed as Dominican sisters and there was a new intake for training. A new mission vessel, the MV Demonic, was commissioned. In the Honiara Diocese, at Tenaru the Apostolic Centre was opened to train local leaders for church work at all levels. A new chapel was blessed and opened at the novitiate house of the Daughters of Mary Immaculate. At Tarapaina in Small Malaita a new hospital was built. Clinics for teaching family planning by a natural method were inaugurated. Several students were sent abroad for higher studies and the number of pupils in Catholic secondary schools rose to 310. There were 779 pupils in Catholic senior primary schools and 1,669 in junior primary schools. The Honiara Diocese was running fourteen dispensaries and eight clinics in rural areas with a total of eighty-seven beds for patients. (AR 1973, 111)

In the Gizo Diocese in 1974 a novitiate for training Solomon Islanders as Dominican priests and brothers opened at Moli, Choiseul in April. St. Joseph's Catechetical Centre was also inaugurated there. The Centre was also engaged in translation of liturgical texts, and it published a series on roneoed booklets in three languages for use by catechists in the villages. In the Honiara Diocese, St. Joseph's Catholic Secondary School at Tenaru was fully established. The School for Catholic Leaders at the Apostolic Centre at Tenaru was in its second year and had thirty students. It was hoped that within a year they could upgrade the Centre with a full staff of catechetical and theology trained teachers. Indigenous staff were being trained overseas, and one priests returned from the University of Papua New Guinea where he studied anthropology. Several staff had been in the Philippines to study catechism and on their return they ran intensive courses to train catechists in the districts of the Diocese. Local sisters took over more posts; their congregation in 1974 was fully organized according to Church rules and they had their own Superior. Among the sisters were two first grade teachers and another studying at the University of the South Pacific in Suva. The number of local clergy was small, but more were expected in 1975. There were three priests at the seminary in Bomana near Port Moresby, two in Suva and others in a minor Seminary at Rabaul. (AR 1974, 116-117)

In 1976 the Solomons was visited by Cardinal Rossi, Prefect for the Propagation of the Faith, who was on his way to Papua New Guinea. He was the most senior member of the Catholic Church to have visited the Solomons to that date. (SND 20 Aug. 1976)

Related entries

Published resources

Books

- Edridge, Sally, Solomon Islands Bibliography to 1980, Institute of Pacific Studies, University of the South Pacific; Alexander Turnbull Library; Solomon Islands National Library, Suva, Wellington & Honiara, 1985. Details

- Fox, Charles E., Lord of the Southern Isles: Being the Story of the Anglican Mission in Melanesia, 1849-1949, Mowbray, London, 1958. Details

- Golden, Graeme A., The Early European Settlers of the Solomon Islands, Graeme A. Golden, Melbourne, 1993. Details

- Kabutaulaka, Tarcisius T., Footprints in the Tasimauri Sea: A Biography of Dominiko Alebua, Institute of Pacific Studies, University of the South Pacific, Suva, 2002. Details

- Laracy, Hugh M., Marists and Melanesians: A History of the Catholic Missions in the Solomon Islands, Australian National University Press, Canberra, 1976. Details

- McCabe, Lawrence, Melanesian Stories: Marist Brothers in Solomon Islands and Papau New Guinea, 1845-2003, Marist Brothers, Madang, 2004. Details

- O'Brien, Claire, A Greater Than Solomon Here: A Story of Catholic Church in Solomon Islands, Catholic Church Solomon Islands Inc., Honiara, 1995. Details

- Wiltgen, Ralph M., The Founding of the Roman Catholic Church in Oceania, 1825 to 1850, Australian National University Press, Canberra, 1981. Details

Journals

- Solomons News Drum, 1974-1982. Details

- Solomon Star, 1982-. Details

- British Solomon Islands Protectorate (ed.), British Solomon Islands Protectorate News Sheet (NS), 1955-1975. Details

Reports

- British Solomon Islands Protectorate, British Solomon Islands Protectorate Annual Reports (AR), 1896-1973. Details

Images

- Title

- Catholic Sisters and school girls at Wanoni Bay, Makira Island, 1920s

- Type

- Image

- Date

- 1920s

- Source

- Raucaz 1928

- Title

- First house of Catholic missionaries at Visale, Guadalcanal,1900s

- Type

- Image

- Date

- 1900s

- Source

- Raucaz 1928

- Title

- Reinforced concrete bridge built at Visale Mission by Brother Roberto, the first of its type in the Solomons.

- Type

- Image

- Date

- 2011

- Source

- Clive Moore

- Title

- Stone church built at Visale Catholic Mission, Guadalcanal. It was destroyed in an earthquake in 1926.

- Type

- Image

- Date

- 1920s

- Source

- Raucaz 1928

.png)