Place: Ontong Java

- Alternative Names

- Lord Howe Atoll

Details

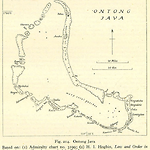

Ontong Java (Lord Howe) is the largest atoll and one of the most remote of the Polynesian outliers in the Solomon Islands. The common name used by Polynesians is Luaniua, but strictly speaking this applies only to the main island, which makes Ontong Java a more useful name for the whole atoll complex. The atoll lies 555 kilometres from Sikaiana Atoll and 250 north of Isabel Island, and over the years it has been assigned to several different administrative districts, the most recent being Malaita Province. The Ontong Java Atoll Group, one of the largest in the world, consists of 120 small, low coral atolls that enclose a vast lagoon extending seventy kilometres from Luaniua in the southeast to Pelau in the north. The two largest islands, Luaniua and Pelau, have the largest communities, which operate separately but resemble each other. The other islands in the atoll chain were initially used as fishing bases. In 1911, Luaniua had about eight hundred people and Pelau about four hundred. According to anthropologist Ian Hogbin's (q.v.) 1920s and 1930s studies, the population was descended from a mix of people who had migrated north from central Polynesia via other Polynesian outliers. Tim Bayliss-Smith suggests that the first populations arrived about two thousand years ago. (Hogbin 1929, 1930-1931, 1930a, 1930b, 1934, 1939a; Bayliss-Smith 1975; Shapiro 1933)

Sikaiana and neighbouring Ontong Java were first settled at the time of the migration south of the Austronesians who eventually became the Polynesians. The people were used to changes brought by outsiders-particularly Samoans, Tongans and Gilbert Islanders-through drift and deliberate voyagers from Micronesia and out of southern Polynesia. Sikaiana and Ontong Java regularly interacted with the other Polynesian outlier atolls to the north: the Nukumanu (Tasman) Islands, fifty-three kilometres north of Ontong Java, and just within modern Papua New Guinea, and the Carteret (Kilinailau or Tulun) Atoll north of Buka Island and the Mortlocks 209 kilometres northwest of Ontong Java, both well within Papua New Guinea waters. Ontong Java also has received Micronesian castaways from the Carolines and Apamama, Maiana, Tamana and Arorai in the Gilbert Islands, and from Ocean Island, and Polynesian ones from Niutau in the Ellice Group. Woodford suspected that other drift voyagers had arrived from Rotuma Island, politically part of Fiji since 1881. (Woodford 1916, 32) These atolls all carried populations of a few hundred, which fluctuated with famines or introductions of disease.

Ontong Java was probably sighted by Mendaña on 23 January 1568, since he named nearby Candlemas (also Candelaria or Kewobua) Reef before his expedition moved on to Isabel and Guadalcanal. La Maire and Schoutehn may also have sighted the atoll on 20 June 1616. Abel Tasman gave the group its name in 1643, probably from the Malay word untung, meaning 'lucky' or 'fortunate'. The translation would thus be 'Java luck' or 'good fortune'. (Woodford 1909b) Spaniard Maurelle passed by Candelaria Reef in 1781. In 1791, British Captain John Hunter, second in command of New South Wales, travelling on the Dutch ship Waaksambeyd, named the atoll group after Lord Howe, although the name is now rarely used since there are other Pacific Islands with that name. (Woodford 1916, 31)

The first recorded visit from a whaler to Ontong Java was in 1828 when the John Bull brought a native castaway home, which led people to welcome subsequent visitors. Whalers continued to visit in the 1830s. During the nineteenth century, Ontong Javans increasingly interacted with outsiders, particularly traders, whalers and predatory labour recruiters. (Bennett 1987, 39) The first trading ship to arrive was the James Birnie, seeking bêche-de-mer in January 1875. At that time Luaniua's chief was Keoraho. A dispute over payment of labour led to the killing of all but one of the white crew, while Solomon Islanders from the ship escaped in a small boat. (Woodford 1916, 32-33) Ontong Javans suffered several famines between about 1860 and 1880. (Hogbin 1930-1931, 46, 1929) They also participated in the labour trade in quite large numbers, considering the small population. Records show that from the early 1870s to the 1890s, 112 went to Queensland as indentured labourers, and thirty-two went to Fiji. (Price with Baker 1976, 116; Seigel 1985)

The society became more stratified in the late nineteenth century, and on both Luaniua and Pelau more powerful paramount chiefs emerged, called he ku'u, as did more powerful spiritual leaders, called maakua. The he ku'u (which could be translated in English as 'king') headed a system that was acceptable to German and then British colonial authorities. He ku'u Uila ruled Luaniua from about 1878 to 1905 and proved able to meet challenges to his power from resident copra traders and from the German and then British governments. He encouraged whole islands to be planted with coconut palms and strengthened the power of women via property inheritance. (Christensen 2010)

Between 1893 and 1899, Ontong Java was part of German New Guinea, but Sikaiana was not, although the British did not claim it until 1897. When HMS Torch visited in 1900, the population was estimated at between two and three thousand. On that visit Resident Commissioner Woodford (q.v.) officially claimed the atoll as part of the Protectorate. In late 1913 he returned and stayed for a week. (Woodford 1916, 31-32; Hogbin 1930-1931, 45) German traders established a permanent station on Ontong Java in 1895. There were two German stations there in 1900, and until 1942, German, Swedish, British or Australian traders were in constant residence. One of the best known was Harold Markham (q.v.), there from 1908 to 1915, who married the daughter of a local chief. Until 1914, the Resident Commissioner visited only occasionally, but that year District Officer J. C. Barley spent a month or two on the atoll and began to visit more regularly. Once the British Protectorate began to assert its authority, the government sided with one chiefly faction, led by Maekaike; he was accepted as chief in 1921 and the British made him a Headman. In 1936, the position passed to his cousin and in 1940 to Maekaike's son Aisa. Meanwhile, traders still operated there and controlled most external relations. (Christensen 2010, 34, 38; Hogbin 1929, 89)

Missionaries tried to establish themselves on Ontong Java, but in 1911 Methodist missionary Ernest Shackle was removed for interfering with the people's religious objects. (Evening Sun, 10 Jan. 1911) Anthropologist Ian Hogbin (q.v.) spent several months on Ontong Java in 1927 and 1928 studying transition rituals. (Hogbin 1930a; Hogbin 1930b) In 1928 there were 352 males and 693 females there. Harold Markham estimated the population during his years there at around five thousand. (Hogbin 1930-1931, 45) Native Medical Practitioner Geoffrey Kuper spent time there in 1939 and counted 588 people, a decline of over 15 percent since Hogbin's 1920s visit. (Hogbin 1939a) There were no large migrations that could explain the decline, so presumably it was caused by diseases.

During and after the Second World War, Ontong Java was largely cut off from the market economy. After 1952, a resident trader was replaced by regular visits by trading ships out of Gizo in Western District or Honiara. The effect of this was the replacement of the natural vegetation by coconut plantations, and by the 1960s the economy had been completely transformed. A cash economy emerged based on production of copra, trochus and fish, with bêche-de-mer added to the mix in the 1970s. (Christensen 2010, 36)

After the war, a District Officer encouraged the chiefs to consult with the heads of major lineages in decision-making, probably hoping to lay the ground for introducing a Native Council. In 1965, Aisa abdicated his power as Headman in favour of a new Luaniua Local Government Council. When he died in 1967 his chiefly position passed to his brother Patrick Keopo. The Protectorate Government promoted the Council as the only legitimate form of government and instituted similar changes on Pelau. By independence in 1978, a united Area Council had been created for Ontong Java. (Bayliss-Smith et al. 2010, 59-61) Malaria eradication since the 1960s has enabled a demographic recovery. Andreas Christensen estimated the 2007 population as 1,850 with another seven hundred living off the atoll. Most of the latter lived in the Lord Howe settlement in Honiara, with others domiciled on nearby Nukumanu (Tasman) atoll within Papua New Guinea. The Melanesian Brotherhood (q.v.) introduced the Anglican Church in 1933. (Christensen 2010, 34, 38)

Several substantial ethnographic studies have been carried out on Ontong Java. Ernst Sarfert and Hans Damm conducted fieldwork there in connection with the German Scientific Expedition to the Southern Seas, in 1908-1910. Twenty years later, Hogbin carried out fieldwork and published his findings in journals (1929, 1930a, 1930b, 1930b, 1930-1931), his book Law and Order in Polynesia: A Study of Primitive Legal Institutions (1934) and a 1958 book titled Social Change. First in 1970-1972, and returning fifteen years later, British geographer Tim Bayliss-Smith undertook a substantial geographical project. During 2006-2008 the atoll was once more studied, this time by a Danish research team through the Galahea 3 Expedition under the auspices of the Danish Expedition Foundation. (Christensen 2010, 24)

The first permanent buildings on the atoll, a school and a courthouse, were built in 1966. In 1975 Ontong Java asked to leave the Malaita Council and join the Isabel Council. Isabel is closer and more people from Ontong Java lived there than on Malaita, but the change was never made. (NS 11 Aug. 1966; SND 9 Apr. 1976; Bayliss-Smith et al. 2010)

Related entries

Published resources

Books

- Bennett, Judith A., Wealth of the Solomons: A History of a Pacific Archipelago, 1800-1978, University of Hawai'i Press, Honolulu, 1987. Details

- Hogbin, H. Ian, Law and Order in Polynesia: A Study of Primitive Legal Institutions, Christophers, London, 1934. Details

Book Sections

- Bayliss-Smith, Tim, 'The Central Polynesian Outlier Populations since European Contact', in C. Carroll (ed.), Pacific Atoll Populations, University of Hawaii Press, Honolulu, 1975, pp. 286-343. Details

Journals

- Solomons News Drum, 1974-1982. Details

- British Solomon Islands Protectorate (ed.), British Solomon Islands Protectorate News Sheet (NS), 1955-1975. Details

Journal Articles

- Bayliss-Smith, Tim, Gough, Katherine V., Christensen, Andreas E., and Kristensen, Soren P., 'Managing Ontong Java: Social Institutions for production and governance of atoll resources in Solomon Islands', Singapore Journal of Tropical Geography, vol. 31, 2010, pp. 55-69. Details

- Hogbin, H. Ian, 'Ontong Java', The Australian Geographer, vol. 1, no. 2, 1929, pp. 86-91. Details

- Hogbin, H. Ian, 'The Problem of Depopulation in Melanesia as Applied to Ongtong Java (Solomon Islands)', Journal of the Polynesian Society, vol. 39, 1930-31, pp. 43-66. Details

- Hogbin, H. Ian, 'Transition Rites at Ontong Java (Solomon Islands)', Journal of the Polynesian Society, vol. 39, no. 154, 1930a, pp. 94-112. Details

- Hogbin, H. Ian, 'Transition Rites at Ontong Java (Solomon Islands) (Continued)', Journal of the Polynesian Society, vol. 39, no. 155, 1930b, pp. 201--220. Details

- Hogbin, H. Ian, 'Population of Ontong Java', Oceania, vol. 10, 1939a, p. 236. Details

- Shapiro, H.L., 'Are the Ontong Javanese Polynesian?', Oceania, vol. 3, no. 3, 1933, pp. 367-376. Details

- Woodford, Charles M., 'Notes on the Atoll of Ontong Java or Lord Howe's Group in the Western Pacific', Journal of the Royal Geographical Society, vol. 34, 1909b, pp. 544-549. Details

- Woodford, Charles M., 'On Some Little-Known Polynesian Settlements in the Neighbourhood of the Solomon Islands', Geographical Journal, vol. 48, no. 1, 1916, pp. 26-49. Details

Theses

- Christensen, Andreas E., 'Making an Island Living: Continuity and Change on Ontong Java, Solomon Islands', PhD, University of Copenhagen, 2010. Details

.png)

.png)