Concept: Material Culture

- Alternative Names

- Architecture

- Weaving

Details

The oldest extant Solomon Islands art forms are petroglyphs found on Guadalcanal, Vella Lavella and South Malaita. Decorative pottery was made on many islands for thousands of years, but now survives mainly on Choiseul Island.

Just as every man and woman was a gardener, each also developed skills in various crafts. Solomon Islanders have always made elaborate decorations on ornamental combs, necklaces, bags, containers for lime for betel nut chewing, woven belts and armbands, baskets, food bowls, dancing sticks, houses and canoes. These patterns are repeated on tattoos, the most extensive of which are from the Polynesian Islands. (See Body Art) Solomon Island woodcarvings, with mother-of-pearl and other shell inlays, are among the most exquisite in the Pacific, and various traditional designs have become ubiquitous in modern tourist art. Stone carving of ornaments is confined mostly to the Western Solomons, particularly Ranongga and Choiseul Islands. The Solomon Islands National Museum (q.v.) possesses a magnificent large stone sarcophagus from Choiseul.

The Museum houses a significant collection of material culture items, and other large collections of Solomon Islands art are held by the Museum of Mankind in London, the Cambridge Museum of Archaeology and Ethnology, the Museum of the Völkerkunde in Berlin, the Field Museum in Chicago, the Australian Museum in Sydney, Queensland Museum, the Auckland War Memorial Museum in Auckland, the Bishop Museum in Honolulu, and Otago Museum in Dunedin. Much of the following draws from explanatory materials produced by the Solomon Islands National Museum.

Star Harbour on the east coast of Santa Ana is famous for its carvers, who specialised in carved house posts, and decorated canoes and food bowls. Archaeological excavations have uncovered trochus (Trochidae) shell fragments and other decorated items, similar to those from nearby Ugi Island, dating back at least five hundred years.

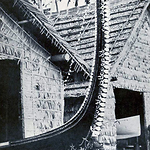

Mortars and pestles were made from wood and stone and used to prepare taro and nut puddings. Stone mortars were made from river boulders on Nggatokae Island in the Western Solomons. Bowls of various designs are made throughout the Solomons. The elaborate shell inlaid ceremonial pots of the Eastern Solomons are well known. Coconut shell and pearl-shell are used on outer islands where wood is scarce. Baskets and mats are made on all islands from pandanus and coconut leaves, often woven with intricate patterns. Net and woven bags are woven or plaited from bark fibres and other plant materials, and they too can be finely patterned. Bamboo food and lime containers were made on some islands with blackened etched designs. Large figure carvings include the roof support posts in buildings at Star Harbour at the eastern end of Makira, which were used to shelter bonito fishing canoes and ancestral relics. The Eastern Solomons also produced large elaborately carved and shell-inlaid food bowls used at large feasts. Sections are inlaid with chambered nautilus and other shells cut into intricate patterns and glued into place with putty made from the 'puttynut' (Parinari glaberrima). Designs include frigate birds and fish and sometimes dogs and sea spirits. Human figure carvings can be found from places such as Arosi on Makira, Malaita and the Weathercoast of Guadalcanal. In the Western Solomons, nguzu-nguzu figures were tied to the prows of canoes to help look out for enemies, reefs and shallows. There are also various styles of traditional currency or wealth (q.v. Forms of Wealth, below). (Starzecka and Cranstone 1974)

Solomon Islanders' major tools were stone and clamshell axes, adzes and hammers. Both the blades and handles varied in size and shape for different tasks, such as canoe making, money manufacture, tree clearing and general food production. On islands with plentiful supplies of hard stone, stone adzes were major tools. The centre of adze manufacture on Guadalcanal was on the Weathercoast. Finished stones themselves were traded to islands where local stone was unsuitable. On some islands without such supplies, such as Rennell and Bellona and Ontong Java and Sikaiana, adzes and scrapers were made from the hard clamshell Tridacna. Bone and fibre tools were also used. The mbarava clamshell plaques in the Western Solomons and the intricate turtle shell cut-outs used for head and breast ornaments (variously called dala, funifunu, or kapkap) were manufactured using stone drills and fibre saws. Digging sticks remain a major gardening tool once the land has been cleared, and gardens are usually fenced with wood or bamboo to keep out pigs.

Pottery

Pottery was manufactured in the archipelago but was not widespread. Most was produced on Choiseul and New Georgia islands in the Western Solomons. There was also a pottery industry on the north coast of Makira, which had died out before Europeans arrived, and pottery was also produced in the Reef Islands. A pottery style linked to the ancient Lapita culture has been found on Anuta Island, which has been inhabited at least since 1,000 to 600 BC. Anuta pots were plain jar and bowl shapes and lacked the elaborate Lapita dentine stamped decorations.

Forms of Wealth

The Solomon Islands have many indigenous forms of wealth, made from shell, porpoise and dog's teeth, feathers and stone, used for mortuary and bride exchanges, compensations, and sometimes commodity exchanges. They equate with European definitions of 'currency' or 'money' to widely varying degrees (sometimes 'valuables' or 'wealth' are more accurate terms). Each island, and sometimes different groups on the same island, had their own valuables. Some rare forms were sacred and kept only by chiefs and priests. Protectorate officers at times calculated the value of traditional forms of wealth and allowed their use to pay fines and taxes. (Akin 1999b; Akin and Robbins 1999)

The Santa Cruz Islands are famous for their red-feather valuables trade. The money is made on Nendö Island in the Santa Cruz Islands and is at the base of the trading system that links the eastern outer islands, as far south as the Reef and Duff Islands. The feathers are usually sourced from the larger islands of Vanikolo and Utupua and come from pigeons to form the underlying bulk and the small scarlet honey-eater (Myzomela cardinalis) to provide the red colour. The honey-eaters are usually plucked of their red feathers and released, though they often die afterwards. Vanikolo and Utupua do not use the red-feather money, although in supplying the basic ingredient they are closely linked into the trade cycle. The feather valuables, known as tevau, are coils that resemble long belts, each containing fifty to sixty thousand feathers. (Davenport 1962; http://www.britishmuseum.org/explore/highlights/highlight_objects/aoa/f/feather_money_tevau.aspx [accessed 16 June 2011]; Friedlaender et al. 2002, 45) The red feather coils are traded to neighbouring islands. They lose value as the feathers gradually wear away. Normal bridewealth payments in the Santa Cruz Islands were ten coils of widely varying values. (Davenport 1962)

Malaita, Guadalcanal and the islands of the Eastern Solomons still use forms of shell valuables made from strung small beads. Malaita had four main types of currency valuables. Three were largely manufactured or controlled by the coastal people: strings of red, orange, white and black shell beads made from bivalves, dog teeth and the teeth of several different species of porpoise and dolphin. A fourth type, called kofu, is strung beads made largely by inland people from tiny coneshells, and is used mostly in Kwaio, 'Are'are, and southern Kwara'ae. Shell body ornaments and special sacred weapons extended the varieties of Malaitan wealth items.

The main form of valuables, bata, was (and still is) laboriously manufactured by clans in Langalanga Lagoon on the west coast and traded as far south as the Banks Group in Vanuatu and Bougainville, New Britain and Manus in Papua New Guinea. Bata consists of polished sections of red, white and black bivalve mollusc shells interspersed with small beads made from seeds (fulu and kekete), strung onto strings of pandanus fibre of various lengths. Ridi is the name for the individual strings, usually in the form of tafuli'ae: ten parallel strings a fathom (six feet, or 1.82 metres) long, separated by wooden or turtle shell spacer bars and decorated with colourful tassels of kekete seeds and, since the nineteenth century, pieces of red cloth. Smaller pieces are used for lesser transactions. Some bata can carry magical properties. The fulu and kekete seeds come from riverine plants, and are usually obtained from the nearby mainland. The most essential shell, the red romu, is found on the reef face about ten fathoms down; they come mainly from Langalanga, around Tarapaina in Maramasike Passage, Suafa Bay and Maana'oba in To'aba'ita, Lau Lagoon, and Mboli Passage, Nggela. Another shell, the white kakadu, is also from reefs but at a different depth, and in the past was usually purchased from Tarapaina or Mboli Passage, Nggela. The third essential shell, the black kurila, is much larger (eight millimetres in diameter) and collected in Langalanga Lagoon or from north Malaita. In some areas shells, particularly romu, have been overfished and are now scarce.

Based on observations going back to Charles Woodford's in the early 1900s, Matthew Cooper described seven forms of Langalanga shell valuables, which vary with colour, bead size, level of finish and number of strings. Bata was traded through intermediaries over long distances, although it was once scarcer than today. (Deck 1934) No longer used for day-to-day purchases, once modern drills were introduced bata became almost ubiquitous in the Solomon Islands, essential for bridewealth payments and other ceremonies. Short strings are also sold as fashionable necklaces throughout the Western Pacific. The processing-cutting, drilling and polishing-is complex, involves the whole community and was incorporated into religious practices. Elaborate rituals (insuring against shark attack) accompanied the diving for shells and collection was limited to certain seasons to conserve supply. Most of the processing was women's work, while males did the diving, long-distance trading and final polishing. Without modern tools, one tafuli'ae is estimated to have taken one woman one month to produce, which gives some idea of its relative value. In polygamous households there was a division of labour, but it is unlikely that any women fully dedicated their time to making bata since they shared many household duties. (Woodford 1908; Bartle 1952; Cooper 1971; Connell 1977)

The 'Are'are and particularly Kwaio manufacture a much smaller white bead called kofu or baniau that is used to make valuables longer than the tafuli'ae. Shorter lengths of kofu are very money-like and are used for commodity exchanges. The Lau Lagoon people also have their own similar forms of shell wealth. Nggela shell wealth is called talina. Shell wealth was also manufactured on Guadalcanal, and an oral tradition says that it was made at Talise on the south coast before Europeans arrived. (Bennett 1987, 14) Shell and teeth wealth is used to pay bridewealth and for other ceremonial exchanges and compensation payments, and is worn as ornaments which sometimes indicate wearers' or their family's special wealth and dignity.

Porpoise and dolphin teeth came mainly from around Fauabu, Bita'ama in the north of Malaita and Walade in the south, although there were also porpoise drives in other areas such as the Langalanga and Lau Lagoons, and among east coast sea people. Annual drives, collectively, killed thousands of the animals. Between one hundred and six hundred might be killed in one drive, each having around 150 usable teeth. Religious rituals accompanied the drives and set seasons ensured against over-fishing. Special stones are hit together underwater to confuse their communication signals and disorient them, and they are driven to shore where they bury their heads in the sand or mud, easy targets for people waiting to club them to death. William H. Dawbin's research in 1965, 1966 and 1968 at Bita'ama, Fauabu and Walande located seven species. In the past, porpoise teeth were the only currency used everywhere across Malaita. (NS 31 Aug. 1968; Dawbin 1966; Notes and Photographs on Porpoise Catching at Auki, Malaita, F. J. Barnett, November 1909, C. M. Woodford Papers, reel 2, bundle 15, 10/31/1-3 and 4/32/1, PMB; Akin 1993, app. 2: Kwaio Shell Money Making and Use of Porpoise Teeth, 1999)

Makira people also hunted porpoises for meat, and for their teeth to use as exchange valuables and body decoration. (NS 15 June 1971; Cromar 1935, 204) On many islands bat and possum teeth are worn in necklaces and collars (the latter called biru on Malaita) and used as currencies. Dog's teeth were also used as currency in the Eastern Solomons and on Guadalcanal. In 1896, trader Karl Oscar Svensen (q.v.) estimated that one-quarter of a million had passed through his hands while trading there since 1890. (Bathgate 1973, 56) Increased supplies enabled inland people to participate more in these wealth exchanges. On Malaita, the lagoon and artificial island-dwellers traded around their island and with other islands, which gave them a large degree of control over supplies of trade items available to inland neighbours.

A final major form of wealth in the past was large rings (up to some fourteen centimetres in diameter) carved from fossilised or recent shells. This shell wealth was used for bridewealth payments, to purchase pigs, land and maritime rights, for compensations, and as grave ornaments and for ritual appeasement. These come from the fossilised Tridacna shell found on the raised coralline limestones of the lagoons. Conus, Trochus or Tridacna shells were also used to make ornaments of some shell ring valuables. In Roviana Lagoon (q.v.) there are two generic categories of shell valuables from pre-colonial times: vinasari, which are patterned decorative shell ornaments once used in rituals and occasionally for barter; and poata, which, as a culturally constructed Roviana genus, included an array of clamshell and shell rings of different diameters, textures and colours and also sperm whale teeth. (Aswani and Sheppard 2003, 64) Similar to most Malaitan shell valuables, New Georgia ones cannot be equated simply with money. They also had ceremonial uses and could transfer ancestral power. Aswani and Sheppard provide a clear description of the different types. Bakiha were the most valuable and were graded by size, texture and the concentration and extent of the yellow to red stain on their surface. Next in value were poata, also known as paota keoro, which come from the upper white sections of fossilized T. Gigas and T. Squamosa shells. Poata circulated widely throughout the Western Solomons as a general currency. They were used also to purchase ritual knowledge, maritime and land rights, for compensations and as offerings to ancestors. The oldest form of shell ring exchanged is the rough edged and unpolished Bareke, which come from both fossilized and live T. suamosa. Aswani and Sheppard suggest that Bareke were not circulated as exchange and 'belonged to a higher spiritual order'. (2003, 65) The smallest and slimmest of the shell valuables are hokata made from Conus shells. These were less valuable and used in barter, marital rituals, as small compensation transfers and were given to chiefs by men for the sexual services of 'ritually designated women'. The last type of shell ring valuable is the smaller hinuili rings made from Conus, Strombus, Mitra, and Terebra shells. Hinuili are 'worn as protective amulets, exchanged within families as gifts, and presented to ancestors and fishing and gardening deities at sacred shrines'. (Aswani and Sheppard 2003, 66)

These shell valuables were used all through the Western Solomons and treasured as far away as Isabel and Bougainville islands. They were stored in shrines or sacred houses where they could not be tampered with or destroyed. Often, they survive in broken form; they were probably broken during ritual transfers of land use-rights. Only the owners can touch the most powerful valuables, after first asking their ancestors for permission. There are observations of their manufacture from as early as the 1880s. Rhys Richards (2010, 98) and Edvard Hviding (1996, 93-95) list three different types of clamshell valuables that were used at Marovo Lagoon, New Georgia: erenge, poata and tinete-in descending order of value-together with the superior currency valuables of kalo (sperm whale teeth) and lave (special ceremonial wickerwork shields). Linked to shell wealth production was control of reefs. Marovo Lagoon (q.v.) was one of the main centres of manufacture.

Choiseulese produced a similar form of wealth called the mbulau sosoto, mbulau patu, mbulau vovo, or vatagotoso, which vary in size from those small enough to fit a child's arm to others with a nine-centimetre internal diameter. These poata were usually reserved for the wealth displays of older men. The ovala, a small shell ring, less finished and not reckoned as wealth, was used to propitiate ancestral spirits. These equate with bareke from Roviana Lagoon. Some poata seem also to have been dedicated to the spirit world. (Russell 1972) Nine cylinders formed one kesa, which were wrapped in ivory palm leaves in sets of three and used as bridewealth payments. A man's status depended on the quality and quantity of the kesa (kisa) he possessed, and the kesa's history.

In 1975, Guso Rato Piko (q.v.), an early Native Medical Practitioner, described the more common types of Choiseul shell valuables: kesa, mbuku, ziku (armlets) and ngazala. Piko also described kesa (kisa), a cylindrical shell wealth that came in different sizes and values. It was old, and said to have been made by the spirit Pongo. People preserved kesa by wrapping them in ivory palm leaves and then burying them in the ground, or by storing them in caves. They came in different denominations, from kalusape, the highest value, possessed by the chiefs. Piko also described Mbarava (or sarumbangara), old clamshell openwork carvings that came from eastern Choiseul and were kept in shrines. The latter was never used as money and was the province of custom priests. (Scheffler 1965b; Piko 1976; Richards 2010; Sheppard, Walter and Nagaoka 2000)

Europeans soon realised the value of these shell valuables and manufactured ceramic versions to use in trade and in the labour trade. (Gesner 1991; Beck 2009; Richards 2010; Russell 1972)

Body Ornaments

Body ornaments can be quite striking, from the traditional dance dress of Santa Cruz men made from clamshell and turtle shell that can be more than a century old, to the intricately carved pieces of turtle shell placed over clamshell disks in forehead ornaments worn on Malaita and Nggela and in the Western Solomons. Men of Malaita and Guadalcanal wear a crescent-shaped piece of gold-lip clamshell (dafi), sometimes decorated with a turtle shell frigatebird or other design. Malaita women wore necklaces of thin oval pieces of clamshell with an etched black design. On Malaita and Guadalcanal, beads made from red, black and white shells, yellow orchid vine and died red fibres are woven or plaited into armbands, combs, belts and other body decorations. Noses and ears were often pierced to hold shell or plaited ornaments. (See also Body Art)

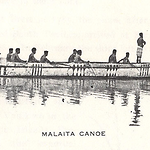

Canoes

Coastal Solomon Islanders have always used canoes, some of great size. Huge war canoes were built from tree trunk bases and extended upwards with planks of wood sewn together with the seams caulked with putty. These could carry around thirty men on long-distance raiding or trading expeditions. They were decorated with shell inlay, carvings and shells, and some had decoration on the bows. Western Solomons tomoko had nguzu-nguzu, a stylized human head at the waterline entrusted to look out for danger. When these canoes were launched there were usually human sacrifices, as many as sixty or seventy. Smaller plank canoes were made in the Central Solomons for fishing.

Other canoes were dugouts six or seven fathoms long (still the measure used) made from hollowed tree trunks. Smaller varieties held two or three men or just children. On Malaita and other islands these were used in the lagoons and river estuaries. The other type of canoe was the sailing canoe found in the Shortlands, in the Eastern Solomons and the Polynesian Outliers. These had matting sails, and the ocean-going versions had a deckhouse made from wood and covered with palm thatch. The dug out hull of the main canoe was augmented with additional planks to create stylised forms that varied from island to island. Non-Polynesian types of sailing canoes are still made in the Shortlands and at Arosi, Makira. Paddles vary in shape and style between islands and sometimes vary with the sex of the paddler, and are often ornamented. They can range from leaf-shaped and pointed to broad with rounded ends. (Tedder 1975)

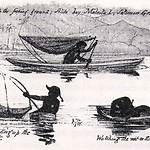

Fishing

In the past, fishing was a major coastal industry and required its own manufactured items, which were often connected to religion. In places, particularly in the east, special festivals marked the beginning of bonito fishing seasons and seasons to hunt dolphins. Fishing methods involved different types of traps, hooks, lures and nets. Bonito hooks were made from pearl-shell with a carved turtle shell hook attached. Leaf curtains were used to create net-shaped fish traps. Fish floats were used in the Eastern Solomons in places like Ulawa and Santa Ana, placed in the sea in a series of six, nine or twelve with stone counterweights tied to their base. On Malaita and in the Eastern Solomons, in shallow areas such as lagoons, garfish were caught by means of kites pulled behind a dugout canoe, which skip a ball of sticky cobwebs across the water. The garfish saw the web glittering on the surface, assumed it was a tiny fish, and when it bit it becames entangled. The kite then fell into the sea and the fisherman knew he had a catch. Coastal platforms were also constructed on many islands, from which fishing took place. Some of these older fishing methods are still used in some places (Cline and Michel 2002, 243-244)

Food Preparation

The most distinctive form of cooking in the Solomons is in earth ovens which is a slow process requiring stones which are heated in a fire and then spread over the floor of a pit. Food is wrapped in leaf packages that are placed inside, more hot stones are put atop them, and the whole is covered with leaves. Water is added to make steam. Quicker cooking is done over embers or in bamboo containers or shells, and in some areas pottery or large wooden bowls with hot stones inside are used. Cooking utensils are usually made from bamboo and shells and graters are made from coral. Root crops and coconuts are pounded with stone or wooden mortars. Wooden containers for food can vary greatly in size and can be plain or richly ornamented with inset shell designs.

Weapons and Shields

Internecine fighting was endemic, using a variety of weapons, mostly bows and arrows, spears, clubs and fighting sticks. Arrows and spears were sometimes tipped with human bone or dipped in poison to cause tetanus or infections. On Rennell and Bellona there were more than a dozen kinds of clubs, and on islands such as Malaita and Guadalcanal there were several types. Shields were usually made from basket materials, woven into designs, or from thin sections of tree trunks or bark. Shell inlaid basket shields depicting human figures were used on Guadalcanal and Nggela and traded to other islands. On Makira, a long-handled curved blade was used to parry arrows and spears. Clubs and spears were sometimes carved or decorated with shell inlay or with incised designs filled with lime powder. On some Polynesian islands slingshots were used with clamshell or stone projectiles. Reef Islanders were experts at this.

As soon as metals arrived with traders in the first half of the nineteenth century weapons began to incorporate iron axe heads, which markedly changed methods of warfare. (Ross 1970; Roth 1998; Waite 2002)

Weaving

There are two basic forms of weaving. One involves simple techniques while the other requires great skills gained over years. Polynesians on islands such as Sikaiana and Rennell and Bellona produce close weaving. People of the Western Solomons produce a more open weave, influenced by Tongan missionaries who introduced new techniques. Gilbertese settlers also introduced to the Solomons new skills in weaving and basketry. Weaving materials used widely in the Solomon Islands are Pandanus leaves, Coco palm leaves, Asama vine (a fern), orchid fibres, banana fibres, tree barks and other plant fibres. Mats, baskets, armbands, fans and bags have been woven using the above materials. Weaving and plaiting can also be found on the handles of combs and ear ornaments.

Despite there being different ways of weaving, the techniques of preparing materials to be woven are relatively similar throughout the islands. For example, with the Pandanus plant, normally the leaf is cut, then rolled and boiled in water for an hour or until the colour disappears, after which the leaves are sun-dried. Some Pandanus leaves have spines on the back and sides that are removed before boiling. Alternatively, the Pandanus leaves may be held over a glowing fire until the colour changes and then rolled and placed in the sun for a week or so until they turn white. They may then be stored until the weavers decide to use them. When the process of weaving begins, the Pandanus leaves may be scraped with a shell to make them pliable, and then split into desired widths.

People in limited areas of the Solomons use a type of cross-weaving loom thought to have originated in the Caroline Islands in Micronesia. These looms were unknown in the Marshall Islands, the Gilbert Islands or the Ellice Group, but were found in the Mortlock Group of Papua New Guinea, Ontong Java, Nuguria, Sikaiana, the Reef Islands and on islands adjacent to Santa Cruz. Only men used them. (BSIP Handbook 1923, 34; Woodford 1916; Roth 1918)

ClothingSolomon Islanders seldom wore much clothing, but some used fibre skirts, bark cloth or woven fibre loincloths. Until the 1970s, fibre skirts were still worn in some inland areas of large islands. On Ontong Java and Sikaiana loincloths were woven of banana fibre on the looms just described. Special long cloths were woven for pregnant women on Sikaiana to ensure the return of a good figure after the birth. Men on Santa Cruz wove black loincloths. On Malaita, pandanus leaves were made into two-surface mats used for sleeping, as umbrellas, to carry items and to wrap the dead.

Bark cloth or tapa is less commonly produced in the Solomons than in other parts of the Pacific, although some comes from Santa Cruz, Isabel and Simbo Islands. It is still in use on Tikopia and Anuta where it is made from the bark of the breadfruit or paper mulberry tree, hammered flat with wooden or stone mallets. It was also manufactured at Makaruka on the Weathercoast of Guadalcanal, and all Malaitan groups made cloth from both mulberry and banyan barks, and some still do. On some islands it was died blue using the fruit of a tree or crushed mussel shells and soaked in sulphur springs in volcanic areas. Other bark cloths from Santa Cruz, Isabel and Simbo were decorated in black, blue and brown. (Richards and Roga 2005; Monberg 1991, 8)

Buildings

Solomon Islands buildings are as diverse as their overall material culture. Most buildings were once made from wood, bamboo and sago leaf thatch, often with palm tree bark or mats as flooring. Each of the nine modern provinces has its own unique traditional building styles, as do different groups in each. Some are round low-walled houses, others rectangular with pitched roofs, sometimes almost reaching the ground, and with decorated panels. Some had dirt floors and others were raised. Men's houses and ceremonial and communal buildings are often larger and more ornate. Houses vary from dwelling houses-often with separate buildings for men and women-to houses to hold sacred objects and perform rituals. Some of the most substantial were vast canoe houses such as the aofa of Santa Ana. These sheltered special canoes for long-distance voyaging and had elaborately carved posts. Boys lived in and were initiated at these aofa to ready them for bonito fishing. (Tedder 1975)

Solomon Islands men and women usually lived at least some of the time in separate dwellings and women on some islands also lived separately during menstruation and after giving birth. Fires inside houses were used for cooking, to preserve artefacts stored on the roof rafters and to provide smoke to deter mosquitoes. Some houses had beaten earth floors or the floors were covered with small rocks or coral, in turn covered with mats. Solomon Islanders also used stone fortifications in some areas.

Over the last century some housing styles were modified with raised floors made from palm trunks skins, more windows and detached kitchens. Many modern office buildings, hotels or churches have adapted the high-pitched roof style of some traditional buildings, and have panels decorated with traditional images or carved posts.

Shrines

Part of this material culture relates to ancestral worship at shrines in designated descent group territories. Ancestral skulls and shell valuables were placed onto altars or in containers and some people maintained special houses to hold skulls collected in raids. In the Western Solomons such skull-houses were made from wood and perched on posts in a tent-shaped structure closed with a carved clamshell mbarava plaque. These sites were used for sacrifices and worship. Peoples of northwest Choiseul constructed ndolo, a hollow stone sarcophagus about a metre high and twelve to eighteen inches in diameter. These contained the cremated bones of chiefs with the bones of lesser people placed in pottery urns around the ndolo. The ndolo often had squatting human figures carved on their sides, which seem to be related to similar objects made as far to the west as western New Guinea.

Musical Instruments

Musical instruments varied from place to place. The most common were slit drums, played singly or in small groups, sometimes accompanying other musical instruments. The drums could also serve to send messages across long distances. Bamboo panpipes were common, some played solo, while others were played by groups at ceremonies and feasts, usually of four, eight, sixteen or more players, particularly on Malaita and Guadalcanal. Much of the music is polyphonic. Panpipes consist of varying numbers of tubes and can be double-banked to provide sympathetic notes. Single transverse tube flutes were used on Malaita and Ulawa and in some Polynesian communities such as on Ontong Java. Rattles were made from hollow nuts attached to dance sticks or tied to the legs or arms of dancers. Basketware fans are used on Ontong Java and other Polynesian islands, beaten against the hand to accompany women's songs. North Malaitans sing to loud rhythms of beaten paired sticks.

Modern Material Culture

Solomon Islanders began to use iron adzes, axes and other tools as soon as they were available in the nineteenth century, often grafted into pre-existing forms of tools or weapons. Surviving examples of these often have elaborate carved sections and shell inlays. Modern art usually includes motifs from older art forms, and carving of deities or spirit figures that would once have been confined to sacred buildings is now displayed in public places such as the National Museum and hotels in Honiara. Solomon Islanders began to make artefacts for barter with sailors on trading, whaling and labour trade ships during the nineteenth century, often simplifying original styles. This practice continued with missionaries, traders, planters and Protectorate staff, and eventually turned into an artefact supply for tourism. Traditional arts are still practiced and on some islands have been deliberately revived as part of cultural preservation practices.

Several carved figure designs have become ubiquitous in the modern Solomons tourist art trade. The nguzu-nguzu, a stylized human head once confined to the prows of canoes from the northwest islands is now one of the most recognized symbols. Another common cultural hero is Kesoko from the Western Solomons, a sea-spirit bird-man with an extended beak. Frigate bird motifs are also common. Most of the wood used in carving today is kerosene wood (Cordia subcordata), ebony (Diospyros), which is an expensive very dense dark brown or black wood, and coconut palm wood. All are sometimes decorated with Nautilus shell inlay. Stone carvings are produced in large quantities on Ranongga Island in the Western Solomons. Woven cane matting in black and white patterns is used as walling, particularly in houses and churches. (Burt, Akin and Kwa'ioloa 2009; Horton 1965, 184; Monberg 1991, 419, 420; information from the Solomon Islands National Museum, Aug. 2011; Starzecka and Cranstone 1974)

Related entries

Published resources

Books

- Bathgate, Murray A., West Guadalcanal Report: A Study of Economic Change and Development in the Indigenous Sector, West Guadalcanal, British Solomon Islands Protectorate, Department of Geography, Victoria University, Wellington, New Zealand, 1973. Details

- Bennett, Judith A., Wealth of the Solomons: A History of a Pacific Archipelago, 1800-1978, University of Hawai'i Press, Honolulu, 1987. Details

- British Solomon Islands Protectorate, Handbook of the British Solomon Islands Protectorate, Western Pacific High Commission, Suva, 1923. Details

- Burt, Ben, with Akin, David, and Kwa'ioloa, Michael, Body Ornaments of Malaita, Solomon Islands, British Museum Press, London, 2009. Details

- Cline, Dennis, and Michel, Bob, Skeeter Beaters: Memories in the South Pacific, 1941-1945, DeForest Press, Elk River, Minn., 2002. Details

- Cromar, John, Jock of the Islands: Early Days in the South Seas: The Adventures of John Cromar, sometime Recruiter and Lately Trader of Marovo, British Solomon Islands Protectorate Told by Himself, Faber & Faber, London, 1935. Details

- Horton, Dick C., The Happy Isles: A Diary of the Solomons, Originally published: 1965, Heinemann, London, 1965. Details

- Monberg, Torben, Bellona Island Beliefs and Rituals, Pacific Islands Monograph Series No.9, University of Hawai'i Press, Honolulu, 1991. Details

- Richards, Rhys, and Roga, Kenneth, Not Quite Extinct: Melanesian Bark Cloth ('tapa') from Western Solomon Islands, Paremata Press, Wellington, 2005. Details

- Scheffler, Harold W., Choiseul Island Social Structure, University of California Press, Berkeley, Calif., 1965. Details

- Starzecka, Dorota C., and Cranstone, B.A.L., The Solomon Islanders, British Museum Publications, London, 1974. Details

Book Sections

- Gege, Jackson, 'Clan Valuables of Guadalcanal', in Ben Burt and Lissant Bolton (eds), InThe Things We Value: Culture and History in Solomon Islands, Sean Kingston Publishing, Canon Pyon (UK), 2014, pp. 62-65. Details

- Guo, Pei-yi, 'Bata The Adaptable Shell-Money of Langalanga, Malaita', in Ben Burt and Lissant Bolton (eds), InThe Things We Value: Culture and History in Solomon Islands, Sean Kingston Publishing, Canon Pyon (UK), 2014, pp. 55-61. Details

- Robbins, Joel, and Akin, David, 'An Introduction to Melanesian Currencies: Agency, Identity, and Social Reproduction', in David Akin;Joel Robbins (ed.), Money and Modernity: State and Local Currencies in Melanesia, University of Pittsburgh Press, Pittsburgh, 1999, pp. 1-40. Details

- Samou, Salome, 'Santa Cruz Feather-Money', in Ben Burt and Lissant Bolton (eds), InThe Things We Value: Culture and History in Solomon Islands, Sean Kingston Publishing, Canon Pyon (UK, 2014. Details

- Waite, Deborah, 'Exploring Solomon Islands Shields: vehicles of Power in changing Museum Cotexts', in Anita Herle (ed.), Pacific Art: Persistence, Change and Meaning, University of Hawai'i Press, Honolulu, 2002, pp. 180-190. Details

Edited Books

- Akin, David, and Robbins, Joel (eds), Money and Modernity: State and Local Currencies in Melanesia, University of Pittsburgh Press, Pittsburgh, 1999. Details

- Burt, Ben and Lissant Bolton (eds), The Things We Value: Culture and History in Solomon Islands, Sean Kingston Publishing, Canon Pyon (UK), 2014. Details

Journals

- British Solomon Islands Protectorate (ed.), British Solomon Islands Protectorate News Sheet (NS), 1955-1975. Details

Journal Articles

- Aswani, Shankar, and Sheppard, Peter, 'The Archaeology and Ethnohistory of Exchange in Precolonial and Colonial Roviana: Gifts, Commodities, and Inalienable Possessions', Current Anthropology, vol. 44, Supplement, 2003, pp. S51-S78. Details

- Bartle, J.F., 'The Shell Money of Auki Island', Corona, vol. 4, 1952, pp. 379-83. Details

- Connell, John, 'The Bougainville Connection: Changes in the Economic Context of Shell Money Production in Malaita', Oceania, vol. 48, no. 2, December, pp. 81-101. Details

- Cooper, Matthew, 'Economic Context of Shell Money Production in Malaita', Oceania, vol. 41, no. 4, June, pp. 266-276. Details

- Davenport, William H., 'Red Feather Money', Scientific American, vol. 206, no. 3, 1962, pp. 94-103. Details

- Dawbin, W.H., 'Porpoises and Porpoise Hunting in Malaita', Australian Natural History, vol. 15, no. 7, September, pp. 207-211. Details

- Deck, Norman C., 'Letter to the Editor', Oceania, vol. 5, no. 2, 1934, pp. 242-245. Details

- Friedlaender, Jonathan S., Gentz, Fred, Green, K., and Merriwether, D.A., 'A Cautionary Tale on Ancient Migration Detection: Mitochondrial DNA Variation in Santa Crux Islands, Solomon Islands', Human Biology, vol. 74, no. 3, 2002, pp. 453-471. Details

- Gesner, Peter, 'A Maritime Archaeological Approach to the Queensland Labour Trade', Bulletin of the Australian Institute for Maritime Archaeology, vol. 15, no. 2, 1991, pp. 15-20. Details

- Piko, Guso, 'Choiseul Currency', Journal of the Cultural Association of the Solomon Islands, vol. 4, 1976, pp. 96-110. Details

- Richards, Rhys, 'Ceramic Imitation Arm Rings for Indigenous Trade in the Solomon Islands, 1880 to 1920', Records of the Auckland Museum, vol. 47, 2010, pp. 93-109. Details

- Ross, Harold M., 'Stone Adzes from Malaita, Solomon Islands: An Ethnographic Contribution to Melanesian Archaeology', Journal of the Polynesian Society, vol. 79, no. 4, December, pp. 411-420. Details

- Roth, Henry L., 'Spears and Other Articles from the Solomon Islands', Journal of the Royal Anthropological Institute of Great Britain and Ireland, vol. 11, 1898, pp. 154-61. Details

- Russell, Tom, 'A Note on Clamshell Money of Simbo and Roviana from an Unpublished Manuscript of Professor A.M. Hocart', Journal of the Solomon Islands Museum Association, vol. 1, 1972, pp. 21-29. Details

- Sheppard, Peter, Walter, Richard, and Nagaoka, Takuyu, 'The Archaeopogy of Head-Hunting in Roviana Lagoon', Journal of the Polynesian Society, vol. 109, no. 1, 2000, pp. 9-38. Details

- Woodford, Charles M., 'Notes on the Manufacture of the Malaita Shell Bead Money of the Solomon Group', Man, vol. 8, 1908, pp. 81-84. Details

- Woodford, Charles M., 'On Some Little-Known Polynesian Settlements in the Neighbourhood of the Solomon Islands', Geographical Journal, vol. 48, no. 1, 1916, pp. 26-49. Details

Theses

- Beck, Stephen, 'Maritime Mechanisms of Contact and Change: Archaeological Perspectives on the History and Conduct of the Queensland Labour Trade', PhD, James Cook University, 2009. Details

Images

.png)

- Title

- A Santa Cruz Weaver, Te Motu Island (Santa Cruz Group)

- Type

- Image

- Date

- 1906

- Source

- Anglican Church of Melanesia

- Title

- 'Are'are canoe in Maramasike Passage, Malaita Island, 1960s

- Type

- Image

- Date

- 1960s

- Source

- Hugo Zemp

- Title

- Captain W.T. Wawn sketched different forms of fishing at Malaita Island

- Type

- Image

- Date

- 1880s - 1890

- Source

- Wawn 1893

.png)

- Title

- Feather Money-Price of a Girl Bought as Teacher's wife, Santa Cruz Island (Santa Cruz Group)

- Type

- Image

- Date

- 1906

- Source

- Anglican Church of Melanesia

- Title

- Fishing with a net at Malaita Island, with the SSEM's Evangel in the background

- Type

- Image

- Date

- 1920s

- Source

- SSEC